Reviewed by Mat Gleason

Ara Oshagan is a poetic photographer merging the magical happenstance of cinema verite with the elegance of a great still life painter. His new book DISPLACED (Kehrer, 2021) is a return to the Armenian enclaves in Lebanon from whence he fled – a refugee – more than forty years ago.

It takes a certain bravery to reconnect after a lengthy passage of time. Whatever the time frame (Is it twenty years? Thirty?), there comes an undetected moment where one’s new homeland supersedes one’s original homeland and the act of returning carries the weight of the hero arriving at where the journey started.

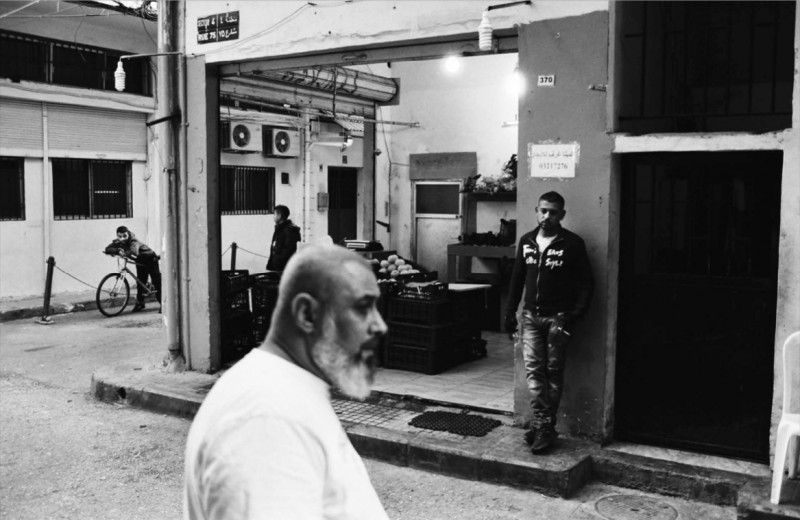

Oshagan went back to the Armenian enclave in Beirut as both a brother and an interloper, an Armenian but an American. His camera caught the intimacy of his familiarity as the hallmarks of his youth were fading heavily away from even memory, and yet there is a trapped sentiment here of being outside, of portraying what one intimately knows but of what one is no longer a part.

The artist has not been excommunicated, he is just distant. A tourist couldn’t take these pictures because even decades later, Oshagan knows the streets, the stores, the rhythm of daily life. A tourist wouldn’t take black and white photos. Absent color, photography caresses the paradox of being both iconic and abstract.

In most of these photos, Oshagan offers us a duality that is in sync with itself. The mysterious, blurry foreground subject and the decipherable background. This optical rhythm is consistent throughout the book. The further away something is from us in these pictures, the easier it is for us to know it. But the foreground interrupts all that. Maybe these disruptions echo the artist’s memories of the civil war, this connection to a world that always has a jarring presence looming amidst the beautiful mundane afternoons at the market and nights with the family.

When he veers from this stance, the results are no less a formal encapsulation of the disjointed marriage between sentiment and terror. A clear foreground shot of a cemetery cross is framed by the background of a bullet-riddled wall – all too familiar for his countrymen, all too dramatic to create a touristic impulse in most viewers. It is important to note that one does not need to be Armenian or Lebanese, speak either language, nor have to have traveled to the Middle East to appreciate the accomplishments of this artist. A photo of a spreadsheet filled in with dates and names is typographically indecipherable to all but a few million readers of Armenian worldwide, but the image Oshagan captures is no less arresting. The mystery, in fact, heightens what is a magically-composed dance of light and shadow, humanity and computation, passages of time and split decisions.

A final meditation on the artist, though, is the subject itself, the generations of Armenians in Beirut, in Lebanon, Armenians worldwide and of course Armenia itself. In Lebanon they were the reliable merchant class before, during and after the horrendous civil war; that was but one of a thousand manifestations of the diaspora. Ara Oshagan bears testament to the ongoing saga from the perspective of a former insider. Perpetually stationed outside the storm, he gazes in with love and admiration, composing a gripping vision that resonates as art first, document second and ultimately his most personal connection to the life he left behind. Ω